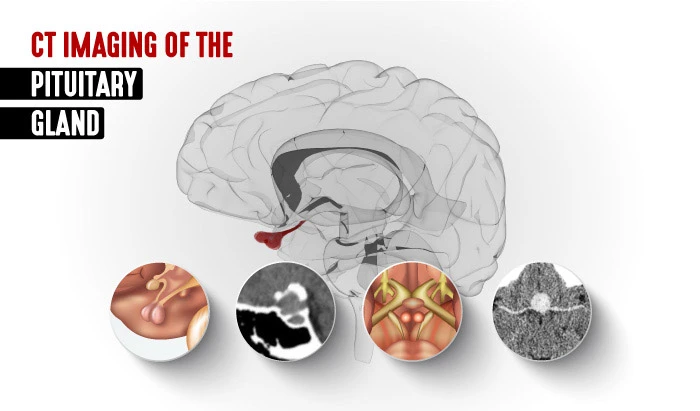

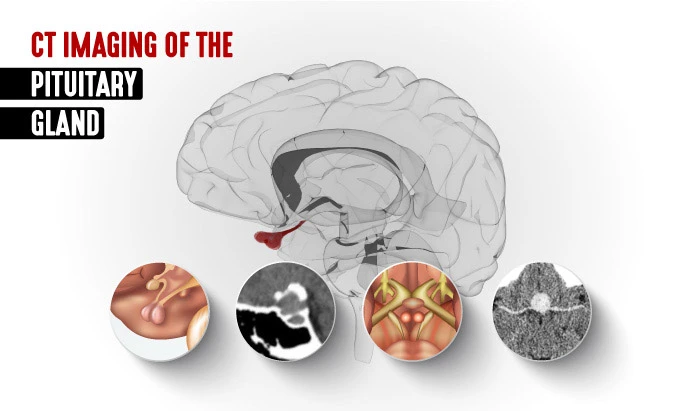

CT Imaging of the Pituitary Gland

This article is part of our series on Computed Tomography (CT). Here, we address pituitary gland anatomy, physiology, and pathologies, as well as the CT scanning protocols for imaging the pituitary gland.

Pituitary Gland Anatomy and Physiology

Also known also as the hypophysis, the pituitary gland is the pea-sized organ attached to the base of the brain. It is referred to as the “master gland,” and it is a major endocrine gland. Though small, it consists of two lobes, the frontal or anterior lobe and the back or posterior lobe. The pituitary is important in controlling growth and development and the function of the other endocrine glands, such as the adrenals and the thyroid. The hypophysis lies in the hypophyseal fossa of the sphenoid bone, which is in the center of the middle cranial fossa. It is surrounded by a small bony cavity known as the sella turcica, which is covered by a dural fold—the diaphragma sellae.

Pathologies of the Pituitary

When abnormal growths develop in the pituitary gland, they often result in too many or too few hormones being released in the body. Most pituitary tumors are adenomas: noncancerous, benign growths which generally do not metastasize to other parts of the body. Adenomas generally arise from the frontal lobe of the pituitary gland. Though they are usually slow growing, they can grow large and put pressure on nearby structures, such as the optic nerve, causing a mass effect in the brain. Pituitary tumors represent approximately 10–15% of intracranial tumors with a 5-year survival rate at approximately 82%.

Carcinomas or malignant tumors of the pituitary can spread to other areas of the body. Pituitary carcinomas are rare diseases with high mortality rates: their low incidence rate presents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for physicians.

Investigating Pathologies of the Pituitary

There are various options for treating pituitary tumors, including removing the tumor, controlling its growth, and managing hormone levels with medications. Often, pituitary tumors go undiagnosed because their symptoms mimic other conditions. They are often found incidentally, when a patient has a workup for other medical reasons.

- Blood and urine tests to assess for an overproduction or deficiency of hormones;

- Vision testing to look for impairment of peripheral vision or sight; and

- Brain imaging, likely a CT scan of the pituitary gland, or possibly an MRI, to look for the location and/or size of a tumor.

Above are two CT images of tumors in the pituitary gland. In the image on the left, there is a well-defined, round isodense lesion noted in the pituitary fossa. Here, you can see the lesion is widening the sella turcica, most likely caused by a pituitary macroadenoma. The image on the right shows a contrast-enhanced macroadenoma.

Using CT to Image the Pituitary Gland

Using axial-acquired helical x-rays, CT generates cross-sectional images of the pituitary gland. Post-processing is used to generate sagittal, coronal, and 3D-rendered images. Adequate contrast, which is needed for image formation, is generated by the differences between the attenuation of bone and that of soft tissue. This makes CT ideal for evaluation calcifications or ossifications within a suprasellar lesion. In fact, it is a better imaging modality than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in its ability to distinguish calcifications within a craniopharyngioma from hemorrhage within a pituitary adenoma since both appear similar on MRI.

- Axial plane with thin contiguous sections

- Intravenous administration of 100 mL of contrast medium

- 120 kV, 200 mA, 2-second scanning time

- Soft tissue algorithm

- Reformatted in coronal and sagittal planes

- Best performed in direct coronal plane

- Maximally extend patient’s neck while patient is either supine or prone

- Allows for demonstration of pituitary abnormalities with radiation dose to lens lower than is possible with axial imaging

Despite the ease of CT in evaluating pituitary gland lesions, it is usually not the first-line imaging modality for evaluating the pituitary fossa. It is important to note that CT has the additional disadvantage of ionizing radiation, which MRI does not. Thus, patients screened for pituitary abnormalities should receive an MRI rather than CT whenever possible. Furthermore, precontrast CT imaging offers little additional diagnostic value, and so avoiding pre-contrast pituitary imaging is recommended. It is important to remember that patients with intracranial lesions often require multiple follow-up imaging studies, for which clinicians should consider the patient’s anticipated cumulative radiation dose.

Treatment

While many pituitary tumors do not require treatment, surgery or pharmacologic treatments are generally the first treatments used. These will depend on the type of tumor, how big it is, and the extent to which it has spread into the brain itself. In the event that these interventions fail, or if there is a recurrence of the tumor, radiation therapy can be the next treatment option for the patient.

References

- https://www.cancer.org/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- Kasper, D.L., et al., eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 19th Ed. United States: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015

- SDworakowska D, Grossman AB. Aggressive and malignant pituitary tumors: state-of-the-art. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018 Nov 1;25(11): R559–R575. doi: 10.1530/ERC-18-0228. PMID: 30306782

- Snyder PJ. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of gonadotroph and other clinically nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas

- Loeffler JS, et al. Radiation therapy of pituitary adenomas

- Winn RH. Pituitary tumors: Functioning and Nonfunctioning. In: Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier; 2017. https://www.clinicalkey.com

- https://www.ninds.nih.gov/